This webpage forms the visual half of my Master's dissertation. The essay, which takes the themes presented here further, can be read by clicking the title below.

A CARTOGRAPHY OF RELATION

Exploring the Role of Island and Archipelago Metaphors in Fostering Relational Perspectives

Please view this webpage in a desktop browser rather than on mobile, as the mobile version does not display the artwork correctly. There is no correct order in which to engage with the essay and this webpage, however the contents of this webpage may make more sense after reading the essay and I would recommend reading it first. References and bibliography are in the essay document should you wish to trace the source of anything included here.

The following comprises a hodgepodge of thoughts, images, drawings, and general ‘thinking out loud’ with island form. Consider it a digital scrapbook or journal - incomplete, evolving, living... The aim of this patching together of patterns is to better understand how island form, particularly archipelagic form, expresses a relational view of the world.

By looking at (and living with) lines, thresholds, horizons, and confluences within the Hebrides archipelago, this work illustrates the literal and metaphorical implications of island form as one that connects and separates, subverting reductionist views of islands as purely isolated places while educating us in the art of paradox - that is, island and archipelagic form shows us that both possibilities (connection and separation) can be harmoniously realised at once.

‘I can change through exchanging with others, without losing or diluting my sense of self’.

This is what archipelagic thinking teaches us (Glissant 2021: 13).

It goes without saying that islands are real places with real beings in them (human and beyond). They are not merely the stuff of intrepid fantasy or the content of luxury holiday magazines. Islands are also the obsession of anthropologists, ecologists and their peers, so when I say that islands yield potent metaphors, I want to add the caveat that their metaphorical status and function does not supersede their lived reality (though the line between these is thin, as I discuss in the essay).

Despite the existence of the term ‘islandness’, there is no essence that can be distilled from or applied to the world’s islands. That said, ‘islandness’ is real to those who experience it, and though the islands of the earth all differ widely, there is a je ne sais quoi that connects them (according to many islanders themselves worldwide).

In the following, you will find my attempts to stretch visual metaphors related to island form - I invert them, combine them, weave them... Some are clear while others are more nebulous, and as such, require an expansion of imagination. This geopoetic experiment invokes ways of subverting cartographic convention and invites new possibilities for understanding human identity and relation alongside our islands and archipelagos, and all the ecosystems, marine and terrestrial, that accompany them.

According to biblical geology the earth was alive: and, like the rest of nature, geography was animated... the idea of islands moving about was by no means as strange to contemporaries as it seems to us…

— John Gillis in Islands of the Mind (2004)

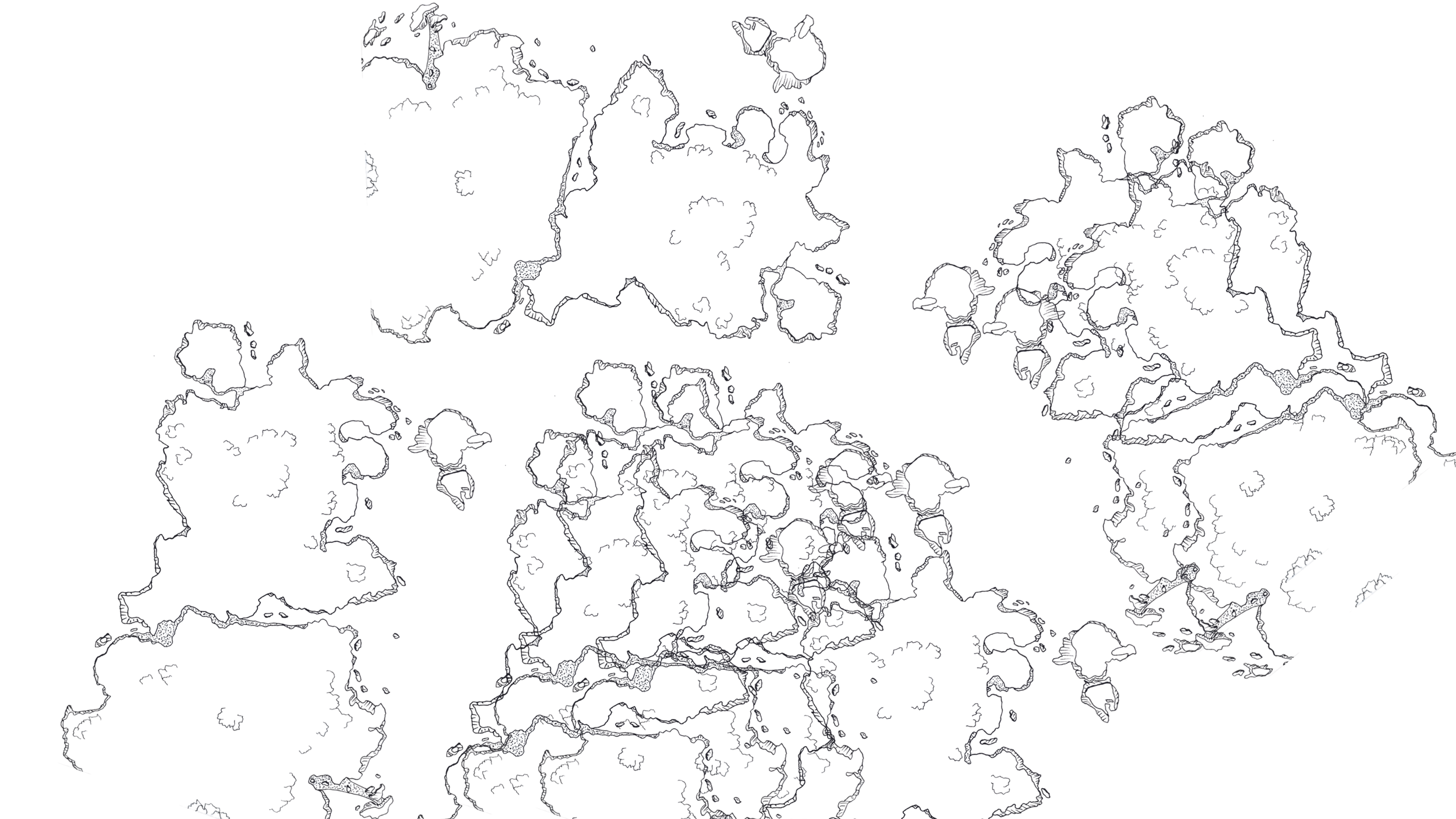

Basic map hand-drawn by me as an experiment in memory. Gometra to the west, Ulva to the east, with Mâisgeir skerry southwest and Eilean Dioghlum, northwest.For the duration of this project, I lived on the Isle of Gometra in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Gometra is 'three islands out' from mainland Britain (which is itself an island within an archipelago). The island is contained by the Isle of Mull and its peninsulas, yet perched right on the edge, surrounded by the Atlantic, and marginally protected by the scattered Treshnish Isles and the isles of Coll and Tiree.

Gometra is currently home to four residents, though the number changes with the seasons. The island has no ferry and is off-grid. With its surrounding waters, it is also home to numerous species, such as the Sea Eagle, Red Deer, Common Seal, and Basking Shark.

While 'islandness' and ‘archipelagicity’ (a term I am using to describe the qualities of an archipelago) cannot be distilled in the study of Gometra alone (or indeed at all), the island expresses many of the qualities of each. Having spent time on other islands, too, it has been illustrative to experience the patterns and connections that appear in each of them.

Every photograph, map, artwork, and so on included in this research emanates from the Gometra landscape, culture and ecology, and from that of its intimate neighbours. My hope is that these visual experiments will run alongside the essay in ways that help visualise some of the concepts and metaphors discussed.

‘Gometra’ is stressed on the first syllable and pronounced to rhyme with comet. But the old Gometra people rhymed it with gormless and slipped in an s and a ch: ‘Gormesdrach.’ Mediaeval charters of the Lords of the Isles render it as ‘Gomedrach.’

— Roc Sandford in Burnt Rain (2023)

The following attempts to paint an intimate portrait of Gometra and the ocean that engenders it with its ‘islandness’. Included are images of ‘noticings’ – subtle features of island life that contribute to a broader sense of islandness and archipelagicity. Old photographs and maps have been included to give a sense of time and show the ‘lived-in’ quality of Gometra, despite its perceived remoteness.

I find maps interesting, despite their colonial associations, because they are a method for knowing, or attempting to know part of a place. Not all map-making endeavours are equal in their intentions or outcomes. You’ll notice that each map of Gometra, ‘official’ or otherwise, is different, illustrating the mutability of island places and our relationship with land and sea more generally.

Maps, like photographs, attempt to encapsulate something, much like the perimeter of an island. Coastlines, frames, and drawn lines contain vital information about the place - where to find water and shelter, who came before, how they worked with the land, the meanings of place names etc.

Maps and images contain ‘partial truths’, much like an island within an archipelago, they provide a piece of a puzzle. We know that ‘the map is not the territory’, but the territory does yield maps... Together, these islands of perception weave an ongoing story of people and place.

This photo of Gometra is a old postcard given to Roc Sandford by Catriona MacDonald, who once lived on the island. It features in Sandford's recent book, Burnt Rain (2023), published by Hazel Press. © Gometra Archive.Angus MacFarland and Charlie MacDonald near Gometra House. Date unknown. © Gometra ArchiveIain MacDonald, Flora MacDonald (no immediate relation) & Jane-Anne MacFarland at Gometra School. 1929. © Gometra ArchiveGometra map drawn by Roc Sandford. © Gometra Archive.Humans make sense of the world using lines, language and metaphor; things which delineate, contain, express, and act as maps for meaning that help us understand the nature of reality and how to navigate it. These cartographic, conceptual, and creative tools provide a container, each word an island, each line a threshold, while metaphor constructs an archipelago of semantic links, affinities and alterities, embodying the relational essence of life in its very anatomy.

— from the essay

An old map of Gometra. A previous resident has translated the meanings of the Gaelic place names underneath in brackets, e.g. Acarseid Mhor is ‘a large anchorage’.Islands and archipelagos are vital places for understanding relationality and our connection to the biosphere, particularly within the context of the Anthropocene, where the effects of climate change, the influence of modernity on indigenous cultures, and the mutability of the ocean-bound landscape gesture towards a correlational enactment of life as opposed to a purely causative one.

— from the essay

There is no world, there are only islands.

— Jacques Derrida

The following are visual experiments with Gometra’s form, using my earlier map as a starting point. Later, I experiment with island form more generally. I have kept descriptions brief because these ideas are more fleshed out in the essay. And I would like to leave some space for interpretation…

The above illustration depicts a section of my Gometra map edited to highlight the liquescent quality of water and a sense of mutability, shifting boundaries, and osmosis between land and water. The image is repeated to represent islands, individuals, atoms, or planets, depending on which way you look at it. Incidentally, islands have historically (and inaccurately) been perceived as metaphorically contiguous with circles or spheres, that is, they were seen as clearly delineated, contained, and, ultimately, simple to grasp (making them attractive places to conquer physically and culturally).

Islands were often perceived as perfect circles, symbols of wholeness (Gillis 2004: 61).

The circle was the symbol of wholeness, cohesion, and good order. Its bounds kept at bay the chaos

that was believed to lurk beyond the circumference (Gillis 2004: 14).

The same image is repeated above to represent islands and archipelagos in a kind of Russian doll formation, whereby islands sit within islands, or archipelagos sit with archipelagos. If the island is not contained, per se, it overlaps with its neighbouring ecosystems, much like an archipelago would.

Above is my Gometra map with reduced detail and fragmentation. Here, the porosity of the coastline is made explicit by gaps in the island's perimeter. Each section could break off and form a new island, which is exactly what happens when tectonic plates shift, or when there is a volcanic eruption. The point where Gometra and Ulva meet becomes unclear, and the island no longer seems to have a separate identity. An island made of islands…

Islands are far from symmetrical, however this visual experiment draws attention to features of the Gometra coastline that may have otherwise been indistinguishable among the novelty that defines its edges. In the essay, I mention ‘the fractality of existence’ - by this I mean things containing other things. The ‘Russian doll’ example gestures at this, as does the lichen experiment further down this page. While islands do not express their form in perfect fractal shapes (such as the Mandelbrot fractal does), they do raise interesting questions around edges, thresholds, points of connection, ‘puzzling together’ pieces, and nested island form, all the way down (more on this in the essay).

Above I have overlayed the Gometra map in various configurations to create a kind of cartographic palimpsest. The island forms are densely packed in some places, creating an impression of complexity and layeredness. It is unclear where the archipelago begins and ends. This metaphor corresponds with the ‘web’ I discuss in the essay.

Island and archipelagic form show us that connection and separation (and what lies beyond or within that) can be harmoniously realised at once and that what separates us also, in the same breath, connects us.

— from the essay

Above are three representations of the point at which Gometra and Ulva, meet. The central satellite image illustrates the position of the water at high tide, where the islands appear to be separated (albeit marginally). The sketch on the left, using dots to represent sand, visualises how the islands are connected at the seabed at low tide. Depending on the level of the tide, the islands are both connected and separated at the same time, however they are always connected at the level of the seabed.

Above is Eilean Dioghlum, a tidal island off the northwest coast of Gometra. Dioghlum (meaning ‘gleaming’) is uninhabited by humans but home to numerous creatures. The top image, which shows the isthmus connecting Gometra and Dioghlum, represents the connectedness of islands, despite surface-level appearances. You could say Dioghlum is in the Gometra archipelago, or it could just be part of Gometra, which is part of Ulva, which is part of Mull, which is part of Scotland, which is part of Britain, which is part of Europe, which is part of Earth...

Above is a photo of the Staffa archipelago, of which Gometra is a part. The Isle of Staffa sits on the horizon, with Mâisgeir skerry in the foreground, and some of the coastline of Gometra. The image reveals yet more layers, points at which forms become apparent, and also at which forms dissolve into the ocean (itself, a form). Beneath the ocean, these rocks are one landmass.

Experimenting with the Staffa archipelago. This image fragments the island forms to show how the rock slopes down into the ocean, while the movement of the ocean continues to shape the landscape.

Under the diamond rock, the wave of the one world (Glissant 2021: 118).

Duality, when understood correctly in all its complexity and contradictions, and when applied at the relevant level of perception, gives rise to life as opposed to destroying it. This is because duality, by its own logic, gives rise to non-duality. Herein, I believe, lies the paradox at the core of relation and of life’s processes, and something which is expressed in island and archipelagic form. This dynamic oscillation between nearness and distance, a dance of proximity and contrast, is at the heart of island form and relation.

— from the essay

The Dutchman’s Cap (Bac Mor) as photographed from the shores of Gometra. Note the connecting strip of land in the middle - it is one island and not two, despite appearances.

Above are several images taken from OS Maps, depicting an aeriel view of Bac Mor. The images have been edited in fractal fashion to draw attention to certain features of the coastline. From above, it is easier to see how the island is connected. From eye-level, depending on the tide, the islands appear to be separate. Changing perspectives enables us to see that both possibilities are correct.

When the undertow of these questions begins pulling you out to sea, remember: migration flows through our blood like the aerial roots of i trongkon nunu. Remember: our ancestors taught us how to carry our culture in the canoes of our bodies. Remember: our people, scattered like stars, form new constellations when we gather. Remember: home is not simply a house, village, or island; home is an archipelago of belonging.

— Craig Santos Perez

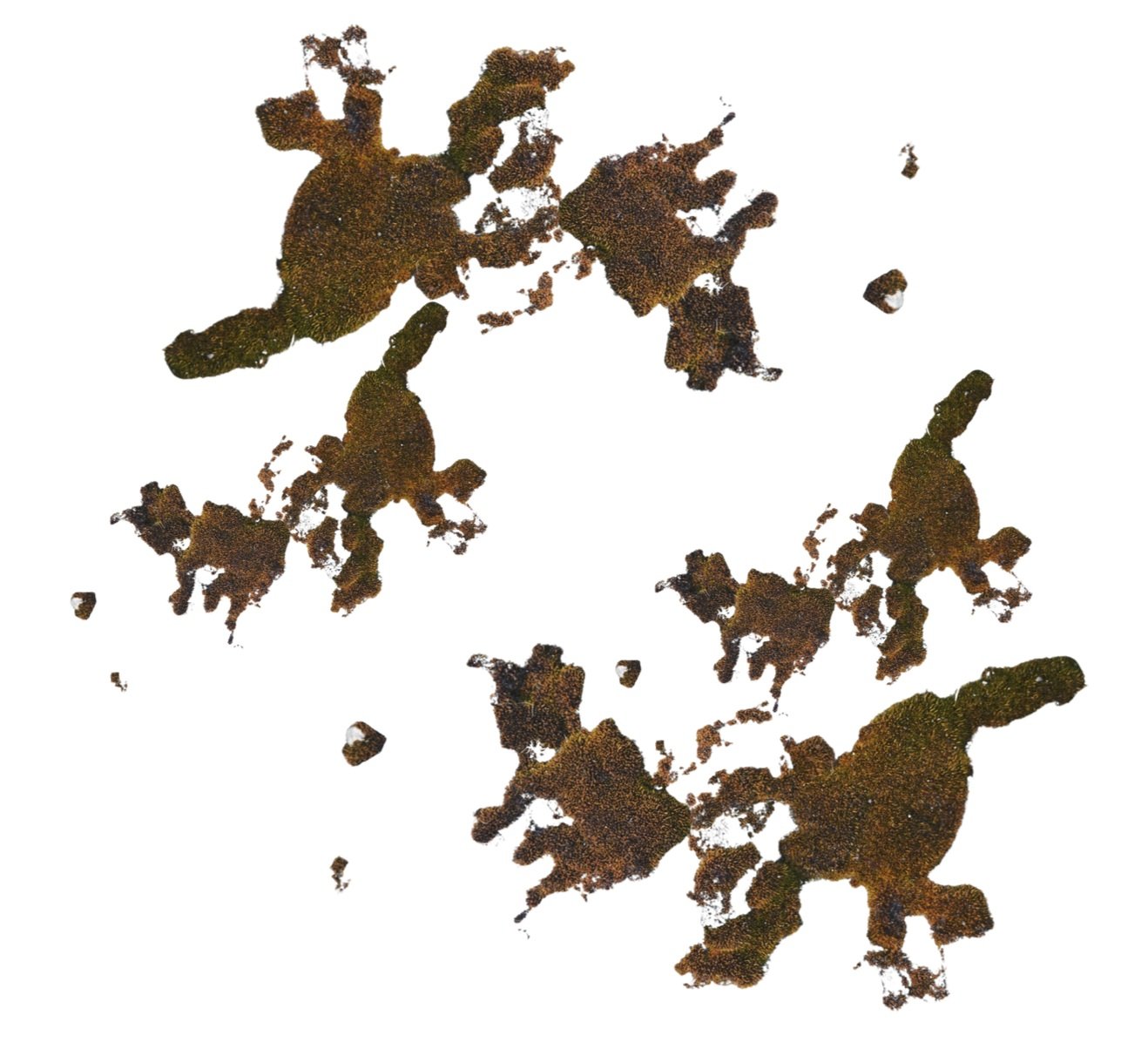

The following images were created by creating a cutout of a made up island using grains of rice. I took the cutout to the beach on the western edge of Gometra and searched for interesting patterns in the landscape. The aim of this experiment was to express Gometra in a new way - its identity is made up of the beings that inhabit it, such as the seaweed, rocks, limpets, flowers and shells that follow…

Are we grounded or afloat? Our lot, it seems, is to oscillate between the two.

— Tim Ingold in Correspondences (2020)

Moving on to more experiments with things found on/in Gometra… these objects include a mussel shell, a limpet shell with a hole in it, a conch shell, a fragment of a crab shell, a beak bone, and the jaw bone of a sheep. The aim of this exercise was to create an archipelago from island objects, illustrating the role each has in forming the identity of the island. While many of these objects can be found across the globe, some cannot, such as the Scottish Blackface sheep bone, or the bird bone, which is from a local bird. Many objects also wash up on the shores of Gometra from islands on the opposite side of the planet.

Scottish birds know Greenland and Africa as well as they know Inverness (White 2006: 76).

What eliminates our perception of an island at one layer and an archipelago at another is our perception, not the absence of the thing from living reality.

— from the essay

Above, the pictured lichen resembles an archipelago, with numerous offshoot islands, and discernible individual circles within itself. Below I have separated the lichen shapes from the rock to see this more clearly. I repeated the shape and created another archipelago structure below.

Below are more images of lichen shapes on Gometra. Each resembles a different island form. The image to the left depicts a shape similar to an atoll, whereas the image to the right shows a contained, circular shape, in line with the historical conception of island form. The central images can be said to represent archipelagos.

The same experiment is repeated below with moss and with lines and patterns I noticed at the beach.

Relation is instead the very process or movement itself, living through and with the disturbances and effects – of colonial legacies, island geographies, oceanic currents, changing shorelines, up to and including elemental forces themselves – that are formed and continuously re-formed to make up (island) life.

— David Chandler and Jonathan Pugh in Anthropocene Islands: Entangled Worlds (2021)

Above I have drawn an island shape on top of a cutout of the ocean from a book. The island that appears above the surface has a complete, unbroken edge, whereas the island ‘roots’ underwater are fragmented and intersecting, playing with the metaphor of an island as a tree, rooted and interconnected below the surface. Islands do not stop at the surface, they do not float (at least not all of them).

They [islands] are invested with ideology, but they refuse to be absorbed by the fantasies and meanings they are encumbered with. They are living spaces, and they are lived in various ways. They offer vivid perceptual experiences, and are sites of spatial play and experimentation. Above all, they offer a geopoetic oscillation between the material energies of words and images, and the energies of the physical world.

— Johannes Riquet in The Aesthetics of Island Space (2019)

Sketch depicting connections between islands via dotted lines.

Islands exemplify a condition of migrancy, a movement of flight—whether purposeful or forced by necessity, or both (Riquet 2019: 73).

Creating island shapes using grains of rice. The image to the left shows one island without a linear perimeter. The image to the right shows two bounded islands.

The island is both bounded and open (Riquet 2019: 58).

Drawing experiment from Tim Ingold’s Correspondences. This exercise was to help visualise turning neatly bounded, circular edges into more novel ones, more accurately conveying the flux at island egdes…

Lines have a material presence; they are not just floating signifiers whose proper place lies

in the domain of images. They are not metaphorical but real (Ingold 2020: 169).

Islandness, in this sense of identity confronting difference, informs primordial issues of philosophy: how, conceptually, we connect and disconnect parts and wholes, for example, and how we connect and disconnect one thing and another.

— Marc Shell in Islandology (2014)

Above is a sketch depicting an archipelago woven together with language.

Metaphorical experience is already the logic of the organic world. Symbolic meaning.

Poetic sleight of hand. The boundless paradox. Within that paradox, we can use language to

experience ourselves as part of the universe of creative references, comprehending

that universe by taking part in it (Weber 2017: 89).

The notion of the rhizome maintains [ ] the idea of rootedness but challenges that of a

totalitarian root. Rhizomatic thought is the principle behind what I calI the Poetics of Relation,

in which each and every identity is extended through a relationship with the Other

(Glissant 1997: 11).

When identity is determined by a root, the emigrant is condemned [ ] to being split

and flattened. Usually an outcast in the place he has newly set anchor, he is forced into

impossible attempts to reconcile his former and present belonging (Glissant 1997: 143).

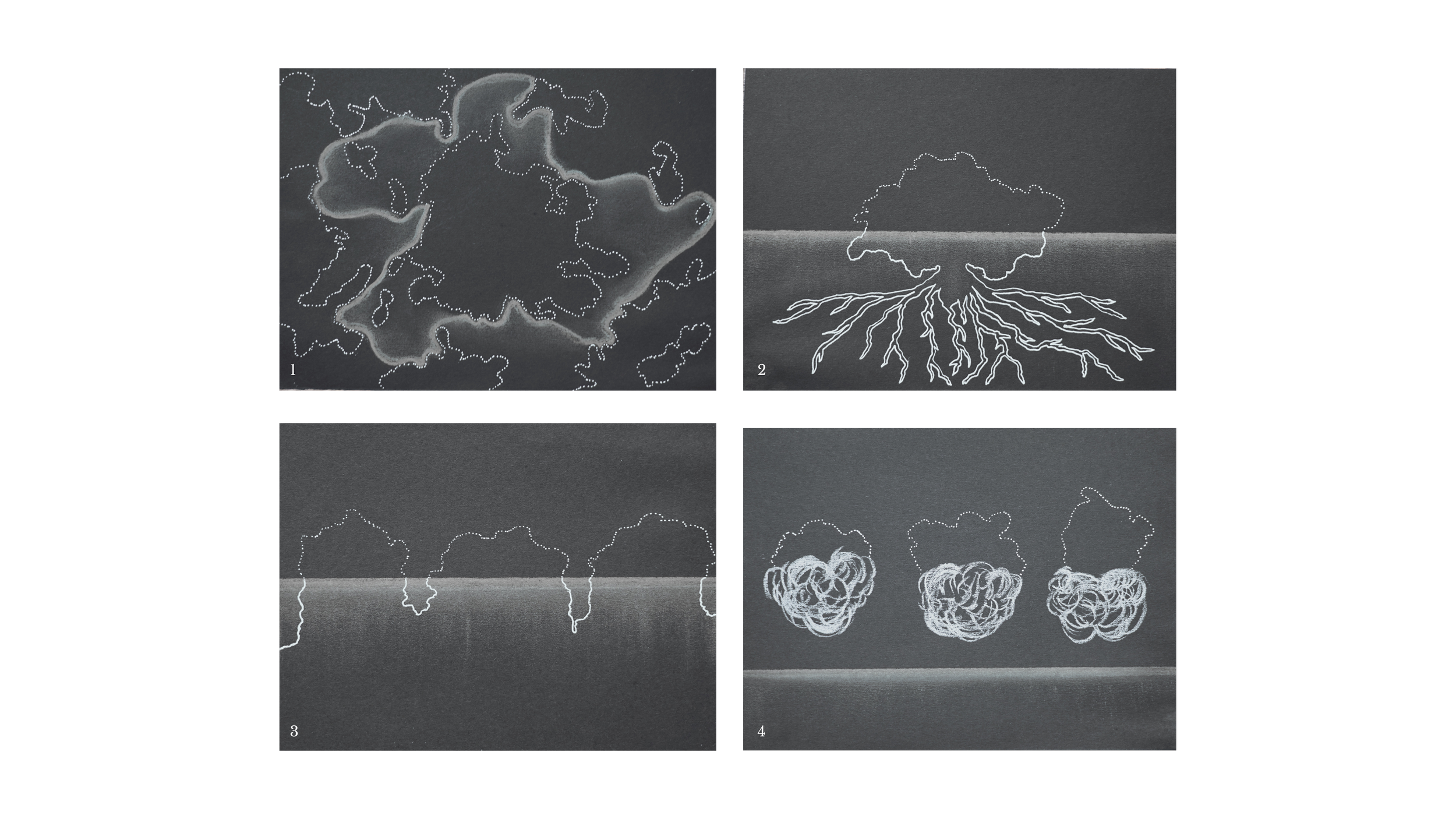

1 - An archipelago with no edge, end, or beginning. This image depicts various islands in an endless archipelago. The shorelines are porous, as represented by dotted lines. Using charcoal, the flow of water, making contact with all the islands, forms a kind of island itself. What is liquid becomes solid. The ocean is no longer merely a ‘place inbetween places’, but is instead a place itself, as implied by a customary cartographic bounded line.

2 - Another iteration of the island as a tree, this time more explicitly resembling a single tree with a centralised root system. Above the surface the island is porous, while below the surface, the roots are solid, representing the solidity of the rock underneath the seabed that connects us all.

3 - Islands here are shown as part of an archipelago, with porous borders and connected roots once more. The lines could be flipped to represent the perceived rigidity of islands above the surface, and the fluidity of islands beneath the surface.

4 - Floating islands. If islands move (as they do), then how do they move? Is the type of movement limited? Might we consider a boat, which floats, to be a floating island? What about the Earth, which floats in space, an island in a cosmic archipelago?

We are all in a way, taut strings, relationships between points, that vibrate, that reciprocate, that reverberate, and out of that comes the creative isthmus that is each one of us.

— Iain McGilchrist in ‘The Coincidence of Opposites’ (2023)